Soundmarks - The Patina Of Memory

- Ryan Burge

- Nov 16, 2019

- 16 min read

Overview

Soundmarks is the overarching title of the soundscape installation featuring the sculptural works of Jenn Garland. Soundmarks - The Patina of Memory refers to the musical activation of the exhibition, a 45 minute ambient work exploring the theme for one night only.

Soundmarks is a collaborative work with visual artist Jenn Garland, commissioned by the 2019 Fremantle Biennale. The Biennale features local and international contemporary artists, with this year's theme being Undercurrents. Probing how ecology influences soundscapes and how soundscapes form an understanding of culture, the work explores the cultural undercurrents of the port city by foregrounding its soundscape as an artefact of cultural activity. We explore this theme through sound using the concept of soundmarks, originally coined by R Murray Schafer. The equivalent of landmarks, soundmarks make one place sound different to another. They define spaces and the activities that happen within them, contributing to our understanding of identity and community. One might think of the blast of a ship horn, tolling of church bells or any other activity that makes sound in a given location. However, as sound is ephemeral and memory of it rarely endures long past its production, its influence on a sense of place is often overlooked.

Beginning with the premise that the way we perceive our surroundings depends on what we hear, as well as what we see, Soundmarks considers alternate ways of knowing a place. It is a site-specific sound installation that reimagines the familiar and explores the unheard to create a nostalgic yet otherworldly space which interrogates cultural memory. The multi-speaker array plays a constantly changing soundscape that never fully repeats, delving into relationships with Fremantle’s coastal environment and history.

Taking sounds from the surrounding areas of the Commissariat Building in which the exhibition is housed such as the Roundhouse, Bathers Beach and South Mole, composer Ryan Burge collected field recordings at these landmarks, and many others, over a 12 month period. Selected recordings are layered, processed and embedded with composed soundscapes. The ‘everyday sounds’ of Fremantle have been submitted to lo-fi sound processing techniques using vintage sound hardware, such as tape, which subsequently loses sonic details as an analogy for omissions in memory. The listener may not be able to distinguish old from new, creating a sense of nostalgia for ‘the now’ or ‘the never-at-all’.

In acknowledgement of the traditional owners of the land, the Whadjuk Noongar people, and the colonial history of Fremantle, known as Walyalup, a minute’s silence is observed at random intervals throughout the composition. This is intended as an act of listening rather than speaking.

The centrepiece of the installation is Jenn Garland’s abstraction of a dusky sunset over the coast of Bather’s Beach, bringing the outside environment inside the building. Twenty flags form an arc, hanging beside each other, to create a vivid colourfield that simulates the Fremantle landmark. A symbol of colonial power, flags have been used to claim territory and impose upon the landscape. Yet here their function is subverted as the landscape is imposed upon the flags, with the same horizon line continuing across their surface. Minimalist concrete sculptures, radios and horn speakers create a monument which riffs on the arches and domes of the local architecture, and draws from significant periods in the formation of Fremantle’s cultural identity, such as the defence of the America's cup in the 1980s and wartime naval operations in the 1940s.

Audiences are asked to reconsider sound within alternate untold histories, and development of expansive knowledge systems within the museum context.

Process, and Development of Rationale

The work began with an on-site visit and research of the use of the building. A conversation with the museum staff led to a discussion about the building function and context. Throughout Fremantle’s colonial history the building has been utilised according to the needs of the government of the day. From storing timber and building products during the construction of the gaol, through the goldrush, to artillery in WWII and now a museum of shipwrecks that pay homage to a defining characteristic that Fremantle has with its port. These various uses became influential in our aesthetic decision-making process when considering materials and compositional techniques.

Throughout the year I made countless visits to Fremantle to listen and record. I focused on the areas surrounding the Commissariat building (now called the Storehouse Gallery), such as Bather’s Beach, The Roundhouse, South Mole, Fremantle Sailing Club and the Port itself. Inevitably this led to a collection of recordings documenting the cultural activity around the coast but other significant areas where sound was collected can be found on Figure 1. Recordings were then catalogued by date and location.

Figure 1. Location visited during the project. Link to explore - https://batchgeo.com/map/bf8feae0037fe6e6c2cc6ab426df143f

To get a sense of the sound of Fremantle from days gone by I spent time reading old newspaper articles on Trove, and spoke with a friend who grew up and lived in Fremantle his whole life. Some of the articles I found often reported on ferocious weather, whilst the conversation with a friend who grew up in Fremantle during the 1970’s conjured sounds of labour and industry down at the pier: crayfishing pots, work tools, yelling, tradesmen and cargo trains, for example.

This lost knowledge of how places used to sound became an important concept of the project. The ephemeral nature of sound means that it does not last long after its production and therefore its influence is often overlooked. The very fact that these histories live on in people's memories almost necessarily induces feelings of nostalgia when recounting or thinking of the sound of a place.

This concept, too, became relevant to the site. With the artwork being installed and exhibited within a museum context it highlights the shift away from factual history, recorded by a small few, to encourage a broader understanding of subjective and plural histories and reconsideration of the role of museums in more expansive and inclusive knowledge systems. Thus, Soundmarks explores concepts such as knowledge systems, cultural identity and historicism.

Image 1. Workings and drafts

Nostalgia is a key aesthetic component for this project. In the music industry, and the culture industry more widely, we see a wave of nostalgia for music genres and old hardware that was critical to their unique sound, such as analog synths and cassette tape recorders, or even in hardware emulators such as vintage tape VST plugins.

This became an interesting point of experimentation in the project. What would would be the perceived effect to process ‘everyday sounds’ such as birds, cars, water, church bells, industry with deteriorated tape? Could a feeling of nostalgia for the banality of daily life be induced and therefore create a moment for reflection on how we develop a sense of individual and cultural identity through sound?

Image 2. L to R: Looking for objects, recording in Kings Square Fremantle, Melville Markets.

I worked a lot with tape for this project. I bought an old portable cassette recorder from the Melville Markets to make field recordings, I made some cassette tape loops, I deliberately degraded the tape by crunching it and reusing it for recording. I loudly played back compositions through the built-in speaker so as to create physical distortions and recorded this in my studio. Finally, I also made some Ableton effects units to emulate old tape.

The process became an analog for a conceptual element of the project. Tape and human memory are similar in the regard that each time they are replayed or recalled small details are lost, omitted or introduced via artefacts. Like old, broken tape, our memory of an event, place or sound usually becomes low fidelity over time. It was this link that led to the decision to make lots of small compositions, that would play randomly, as if they were the collective memories of Fremantle being recalled.

Image 3. Cassette tape loops and vintage tape recorder

Making ‘everyday sounds’ sound interesting, special or unique was an area of investigation with this project. As a soundscape composer, aesthetic questions continually influence decisions on the process. Such questions include what device and format should I record with, what to record, what to edit, which parts of a recording to use, what degree of manipulation and why? An area I personally wanted to explore further in this project was the use of musical tonality with field recordings. For example, what effect does a discordant drone have when combined with a recording of the cranes operating at the port, or a sparse piano melody dotted over the ocean waves. Can

harmony and discord be used to augment or diminish the meaning of a soundmark?

This led to fundamental consideration about the nature and virtue of sound itself. Sounds are signs, and signs carry meaning, and meaning has cultural value. So, how can we use sound to create, subvert, enhance or simply depict cultural value? Soundmarks is an exploration of cultural boundaries, of demarcation and distribution of power, and of the acoustic ecologies that shape how we come to know a place.

Compositional Techniques

I set about selecting field recordings that captured interesting events or contained tonal qualities or engaging timbral qualities. I went through a process of experimentation with each composition to create drones and short ambient sketches. I wanted to create “musical field recordings” through digital signal processing and synth-drones. There are several techniques where I have taken inspiration from well-documented techniques from established composers.

Table 1. Summary of each composition

In Music For Airports, Eno layered transposed loops of the same sample to create odd loop lengths, thereby creating generative-style compositions that have unexpected but reliable results. This is a technique I used a lot, but instead of using a typical instrument I used it on field recordings. http://music.hyperreal.org/artists/brian_eno/interviews/downbeat79.htm

Another technique used was to simulate the processes of William Bassinki’s Disintegration Loops. In this work tape loops are literally disintegrating as they’re being recorded, foregrounding the medium in the composition itself. To achieve this ‘broken tape’ effect I created tape FX units in Ableton by automating pitch and amplitude with sine and noise oscillators and then recorded these onto tape that I had deliberately ruined. The tape was then played back through the in-built speaker at a loud volume so as to capture the distortions of the portable tape player.

An ambient dub techno producer I admire, in particular for the way his music is mixed, is GAS. He foregrounds noise, hiss, resonant pads and subtle shifts in timbre. When there is a bass drum and bassline, this will be mixed in the background as if to sound in the distance. This creates a very cinematic and spacious mix since the listener is not focused on this. I have taken a similar approach with many of the compositions by pushing the music to the background and pulling the field recordings up front. I wanted them to be accompanied by harmonies and melodies and electronic textures, so as to make them more relatable to people. In effect, to aestheticise the benal.

Barry Truax’s work with granular synthesis such as on Riverun and use of resonators to enhance existing pitch in Pendlerdrøm paved the way for the techniques used in some of these compositions. Truax has described the process of granular synthesis as the turning of sound inside out. By this he means that by defying time the listener is able to hear the constituents of the sound, rather then just the surface.

Hildegard Westerkamp’s Into India manipulates field recordings, stitches and layers them with one another and enhances, both conceptually and sonically, with composed material. This work is a concept album that explores cultures through sound, which is a trademark theme of this project.

The Caretaker is a composer that has been described as making hauntological music. Hauntology is usually attributed to cultural theorist Mark Fisher who uses the term aesthetically to describe art that somehow seems out of time. Specifically, art that is influenced by the ‘no longer’ or ‘not yet’. Leyland Kirby’s music is described by Fisher as as a “yearning for the future that we feel cheated out of.” His techniques are starkly simple yet effective, he applies reverb to old vinyl records so as to highlight the age through casting an effect on the medium itself (crackle) but to also place them in a contextual visual environment. Listening to old music with unnatural amounts of reverb somehow allows us to see it as an historical artefact still playing, and relevant, in an alternative universe.

Philosophical Approaches

R Murray Schafer’s philosophy on soundscapes has had a large influence on this project. In fact, soundmarks is a term he coined in relation to describing our relationship to place through sound, as a play on landmarks. And throughout this project I have been conscious of his theory on hi-fi and lo-fi soundscapes; the friction between natural and urban boundaries. Fremantle is a great example of industry vis-a-vis nature.

Pauline Oliveros’ concept of Deep Listening is something I hope to have invoked in the auditor. She explains the difference between listening and hearing as fundamentally about an act of conscious awareness, “the ear hears and the brain listens.”

Max Neuhaus is a ‘sound installation’ artist often credited with first using the term to describe his art. One of his famous works “Time’s Square” is a synth drone that has been playing in a Manhattan drain vent since 1977. However, of more interest for me is his endeavour as a sound artist: “Neuhaus was fascinated by the idea of staging an aesthetic experience that was so embedded in an everyday experience of a place that one could choose to attend the work or simply let it pass by.”

Times Square: https://hyperallergic.com/298871/a-hidden-times-square-sound-installation-returns-to-full-hum/

On aesthetics of sound art http://soundinstallationart.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/neuhaus_potts-alex_momentplace_pp44-57.pdf

Finally, and conceptually important, is the use of 1 minute of silence that is randomly played during the sound installation. The silence not only provides balance in the work but serves a more important purpose in what it signifies. That is, in western cultures a minute’s silence is used to pay respect to those that have passed, but is also a symbolic act to listen rather than speak. As an Anglo Australian I felt it was necessary to acknowledge in some way the context of the building, the city of Fremantle’s history and that the work derived on Whajuk Boodjar.

The Collaboration

Indeed this project was not conceived nor created in a bubble. My wife and co-creator was responsible for the visual aspect of the exhibition. She built the sculptures and conceptualised the visual centrepiece, the arc of flags that simulates the sunset, an act of subverting colonial power by imposing the landscape on the flags rather than the flags on the landscape.

We were able to talk a lot about the project, and with the Biennale Artistic Director, which enabled a key insight for me as a composer seeking to work more in the visual arts as a sound installation artist. Sound, and even more so music is by nature nebulous and abstract. To convey meaning through sound alone can be challenging. For example, most people will probably not hear the destructive process editing of church bells and think how this may be a subversive comment on the power of the catholic church, but certainly this could be easily depicted with a paintbrush. Perhaps this stems from our visual-centric culture, that we “have to see it to believe it”, or maybe we just don’t think so much about sound outside of music. I believe there is an interesting paradox at play between the domains of sound art/music and visual art. Sound can be a problematic medium to convey meaning since it is inherently abstract, whereas visual arts are inherently concrete. This leaves artists in an interesting dilemma where composers can often be overly didactic with their work to ensure its meaning is understood, whilst visual artists try to be less didactic so their work is more ambiguous. In short, I offer the provocation that sound art wants to be more like visual art and visual art more like sound art. Striking the balance here required concerted discussion and decision-making between us. Questions such as “what are we trying to say by including this” and “how does this contribute to the overall concept” were asked time and time again, keeping each other in check by justifying artistic decisions.

Another factor affecting the project was working with the WA Shipwreck Museum. There were strict conditions about what was allowed in the building. A list of all items to be brought in had to be provided and all electrical items had to be tested and tagged (which proved to be quite costly given the nature of the project). One of the stringent conditions was that no organic material was to be brought in. At one point we wanted to bring in sand, thinking this was inorganic, but this had to be frozen for two weeks to ensure it was safe.

The Technical Setup

One of the key issues around a sound installation is the technical considerations. The room is large, at approximately 10m x 15m. There are four columns in the room that join into arches, the floor is polished concrete and the walls limestone brick, so reverb and echo were a concern from the outset.

Image 4. The Storehouse Gallery, empty.

Of course as a sound installation my initial thoughts was one of sound quality. However, since this is not solely a sound installation but also a visual, attention to visual aesthetics was of equal value. Essentially this meant that decisions had to be made with regard to what people would see and therefore how it would be technically constructed.

Image 5. Sound monument of concrete sculptures and found objects

Another guiding principle in the design was to attempt to remove technology from the listening experience. By this I refer to the oft-so witnessed practice of the audience moving around the room to place their head up against a speaker, as if to somehow judge the quality of sound coming from the speaker. This is an inherent issue with installation work, or spatial works, where people are listening to the technology not the content.

And so with these self imposed limitations, Jenn and I decided that the speakers would be housed in the sculptures themselves or be conceptually incorporated. This required passive speakers, small amps and making approximately 180m of cables. With only a small budget we went to swap-meets, garage sales, op-shops and curbside collections to collect speakers. Old horn PA speakers, a ghetto blaster, a WWII speaker and nautical looking objects were used to emit audio.

Controlling the sound is laptop running Ableton, an external audio interface with 10 outputs and 7 amps. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Layout of speakers

Ableton is running in Session Mode with all compositions being direct into the chosen channels based on the sculptural layout and concept. Each channel contains numerous compositions that are played randomly on loop using the Follow Actions function as can be seen in Figure 3. The volume remains relatively low so as to avoid distracting resonances and a swampy listening experience.

Figure 3. Screen grab of the session.

Since the exhibition is invigilated by volunteers, consideration as to the technical requirements for operating the installation were also made. In this instance I have made this the easiest I possibly could, simply using the space-bar to turn the Ableton on/off and to leave the equipment switched on.

Equipment List

1 x PC laptop running Ableton 10

1 x Focusrite 1820

7 x amplifiers

1 x yamaha Sub

1 x surface transducer

7 x 5-inch woofers

2 x 7 inch woofers

2 x tweeters

2 x horn speakers

2 x radios

180m of 0.5mm cable

The Patina Of Memory

The Patina of Memory is a musical activation of the exhibition. This work augments the installation insofar as a score for performance has been developed for small ensemble based on the composed material for the installation. The title alludes to the overarching theme of how memories age and evolve as they’re recalled over time.

The piece is for four performers: bass clarinet, percussion, double bass and electronics. Utilising the custom built spatial array, the 45-minute ambient work is set among the sculptural works of Jenn Garland. As previously delineated, nostalgia is the key feeling that I wish to convey through the installation and also through this work.

The sound installation will stay running for the entirety of the performance at a low volume. The reasons are two fold: The performance extends the installation, and also for practical purposes, so as not to mess with the cabling and setup.

The basic concept for the composition was to create an electroacoustic section from the smaller compositions that make up the installation and then create parts for acoustic instruments. For most of the composition, notes are sustained to creates harmonic drones, highlighting the timbral qualities but also allowing space to contemplate the content of the field recordings.

To enhance the sustain on the bass clarinet, I have a mic that feeds into an fx chain. In the chain is EQ, a resonator, reverb and a limiter. The resonator, set to play the Tonic + m3 + oct + oct&5th, is being altered during the performance to match the bass clarinet pitch. The double bass also feeds into this channel but at a lower volume.

On the cymbals is another mic that feeds into another FX chain. On this chain is EQ, compression, resonator, reverb and limiter. The resonator is set to play a cluster chord when activated. That is tonic + 1st +2st and -1st and -2st.

The desired effect from this setup is to create an ambient work that generally moves and evolves slowly.

Development of the Score

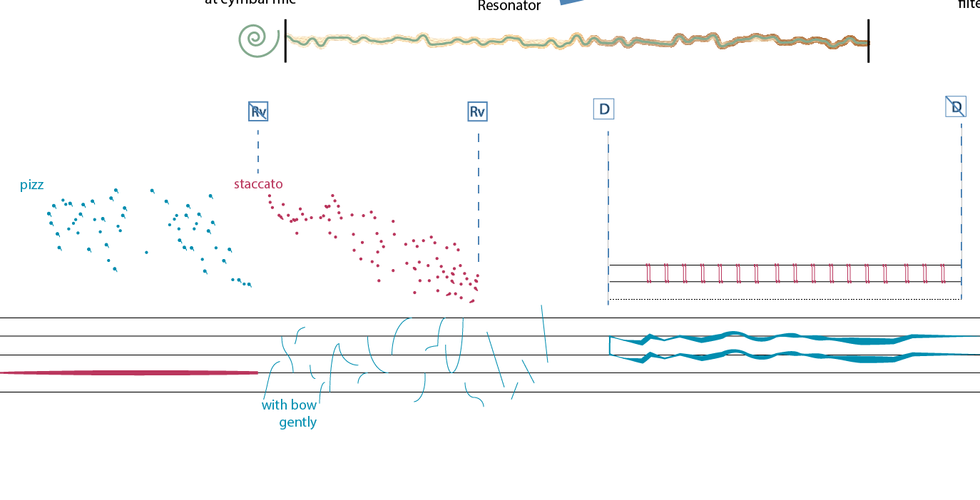

I used a graphical score in the Decibel Scoreplayer so I could coordinate all parts without a conductor and convey concepts not easily communicated with traditional notation. I used a spectrogram as a kind of template to further annotate in Adobe Illustrator.

Stage 1: Arrangement | Ableton

Utilising approximately 36 separate compositions I had put together for the exhibition I created a 46 minute electroacoustic composition. As a loose structural guide I arranged the composition based on sounds collected in proximity to the building, beginning and ending with the Bather’s Beach recordings, of which I feel ocean in this context signifies expansive time and self-reflection. Another arrangement strategy was to use timbral qualities to either create seamless transitions. For example, field recordings with water will sit well with each other and mixed well with the drones.

The electroacoustic composition became the backbone of the arrangement of the acoustic instruments. Using midi, I scored some parts that I was sure I wanted the double bass and bass clarinet to play.

Once satisfied I exported the 46-minute .wav file and the midi parts.

The electroacoustic composition by itself.

Stage 2: Proportional graphics | Sonic Visualiser

In Sonic Visualiser I was able to import the .wav to create a spectrogram. There was a lot of back and forth between Ableton and Sonic Visualiser trying to get only the necessary frequencies. One decision I made was to remove all frequencies below 40Hz and all above 5kHz so as to create a cleaner spectrogram. Once satisfied with the resolution, I exported the whole composition to a .png.

Then I needed to ensure that the midi parts were proportional to the spectrogram. So at first I simply imported into the same project file, but this is not the desired outcome for turning into a png because the midi notes are embedded with spectrogram. So to overcome this problem I created a 46-minute .wav of silence and then imported the midi.

Finally, to ensure I knew where to place the staff lines in the spectrogram I created some guide points based on the lowest G in the bass clef and the highest F in the treble clef. This is a frequency range of approximately 40 Hz to 1.5kHz.

I then exported the midi in .png format. All files are of the same height and length so they’re proportionate.

Stage 3: Drawing in Adobe Illustrator/ Photoshop

I began by making the white parts transparent in Photoshop. This allows for layering images much easier and cleaner when in Illustrator. I lined up all the images in Illustrator on the widest artboard possible so as to allow for the highest resolution and the most practical score possible to read/play over 46 minutes. Then I drew in the staff lines against the midi markers so I had all parts in proportion.

After a short while I realised that the piece was too long to rely on the spectrogram for accurate placement of of graphics and lines. So I created a timer showing each 30 seconds. This sped up the process and removed the guesswork.

I decided to have all parts on the one page so all players can see how they’re interacting with each other. In a reductionist way, the bass clarinet and the double bass are in duet and dual, whilst the same goes for the percussion and electronics.

Instructions:

Tiles of the score

Comments